2009

Cynthia, Eric, "Ilka"

Cynthia, Eric, "Ilka"

Red-Tailed Hawks

by Dorothy Ainsworth

Anvil cloud

Anvil cloud

Galena Canyon

Galena Canyon

Ever hear of Galena, Nevada? Didn't think so. I hadn't either until I spent a summer there in 1969. It's an old ghost town about 10 miles south of Battle Mountain and 44 miles SE of Winnemucca, Nevada. Now you're getting the picture...and you're right, the picture is bleak. It's in the foothills above Battle Mountain in the middle of Galena Canyon, which in turn is in the middle of nowhere. When we were there the population was only five: My husband Ron and I, and our two little kids, Eric and Cynthia...and Oscar, an old hard-rock miner who was a permanent fixture. (The population is now ten.)

The gold mine

The gold mine

Galena had seen better days back in the 1870's and 1880's, when it was a hoppin' town that boasted 250 residents and 100 miners. In the town's short life its mines produced 5 million dollars worth of silver and lead...the latter extracted from it's namesake ore, Galena.

There was also gold in them thar hills, and that's what took US there. My in-laws were in the real-estate business in Reno, and as an investment adventure based on pure speculation they bought the rights to glean whatever gold they could find left in the tunnel and in the tailings from an old mine there. They sent their only begotten son to work the mine for three months or bust. Our home was in Reno, but I didn't mind going along because it was the first (and last) time I would have an extended vacation from waitressing, and the kids were only five and six and would be easily entertained.

Ron, Eric, Cynthia in track loader

Ron, Eric, Cynthia in track loader

We were provided a small livable travel trailer surrounded by tall cottonwood trees for shade. Oscar, who was there to help, was an experienced dynamite blasting man from a bygone era. He stayed in an old dilapidated building, fought off large Norway rats at night, and showed us the fresh scratches on his legs in the morning. He complained about sleep deprivation from the huge rats stomping their feet all night to communicate and told us that when he challenged them with a flashlight, they'd rear up on their hind legs, make growling and hissing noises, and go for his shins.

Little trailer & Ford Fairlane

Little trailer & Ford Fairlane

Ron fixing loader

Ron fixing loader

Oscar

Oscar

Oscar knew how to operate the ore-sifting and ore-washing equipment and how to keep the holding pond full from the natural spring that fed Galena Creek. Ron operated an Allis Chalmers track loader to bring the ore out of the mine, then loaded it into a big dump truck and drove it to a nearby processing shed.

The only modern building in Galena was a concrete-block assay office a hopeful investor built during a previous resurgence of interest in the old mines.

We were determined to bloom where we were planted, so we decided to be very creative and get the most out of our Summer Lampoon Vacation. It helped that we were young and in love, healthy and happy, and interested in science and nature.

It didn't take long to discover that this desolate landscape was literally crawling with life. The kids and I scrutinized beetles and bugs, lizards and snakes, spiders and moths, climbed trees, chased butterflies, started a bird nest collection, found beautiful rocks and precious stones, and played in the run-off water from the mine tailings. Eric and Cynthia had gold-fever too...well, fool's gold...and they got rich quick by filling leather pouches with shiny mica.

Cynthia & Eric playing in run-off water from mine

Cynthia & Eric playing in run-off water from mine

There were old deserted houses to browse through, caves to get lost in, and mine-shafts to fall into everywhere we explored. We even caught trout by hand in a narrow stream with overhanging banks. The wary fish would hide up under the overhang in the roots and that's where we would be able to get a grip on them. But grabbing a slippery fish and hanging onto it are two different things! While we squeezed and giggled, they slimed and wiggled...until they catapulted out of our hands like greased lightning! It wasn't easy, but we managed to catch enough for a big fish-fry.

Cynthia 5

Cynthia 5

Eric 6

Eric 6

My only complaint about the desert was the heat, so I cut off my long thick hair as short as possible, and the kids and I wore bathing suits or less most of the time. There was nobody around to see us except Oscar, and he was busy fighting off real or imaginary rats (depending on how much he had to drink).

Baseball team

Baseball team

Cynthia & Eric in huge cottonwood tree

Cynthia & Eric in huge cottonwood tree

Fish caught by hand

Fish caught by hand

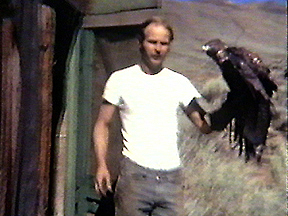

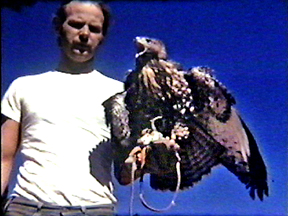

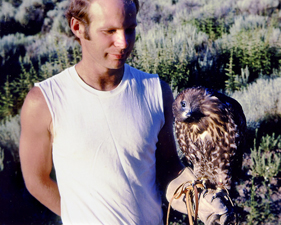

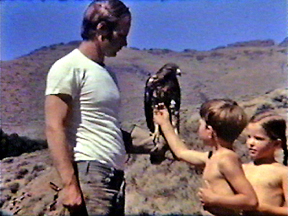

Ron had always been interested in raptors (birds of prey), and had read several books on falcons and hawks, and was particularly interested in falconry. He hoped that someday he would have the opportunity to try out his knowledge and actually train a hawk to hunt. As serendipity would have it, a mother red-tail had made a nest about 50-feet up in one of the cottonwood trees by our trailer. We'd hear her familiar raspy shrill cry all day long as she flew to and fro bringing food to her babies.

After we got settled in for a couple of weeks, Ron decided to climb the tree and take a look in the nest. Just in case there were two fledglings (birds old enough to learn to fly), he took along a pillowcase to nab one. Up up up he bravely went while the kids and I waited nervously at the bottom and warned him, "Hurry, here she comes!" Sure enough there were two feathered adolescents in the nest (six wks. old), so he grabbed one and stuck it in the bag and scrambled down the tree, just before the screaming mama swooped down to peck off his nose. This was no nursery rhyme moment! (We learned later that red-tailed hawks do not attack people and will generally flee rather than defend their nest.)

Dorothy & Ilka

Dorothy & Ilka

Ron had prepared to keep the hawk in falconer's style if his bird-napping was successful. He had converted a small outbuilding into a hawk house (a mews), bought jesses (leather straps) for its feet and had a .22 revolver to hunt rodents with. We named our beautiful girl Ilka, a Hungarian name that we simply liked the sound of.

Ron and I manned the hawk regularly (part of its training to learn to stay on its master's arm) by taking turns walking with it loosely lashed to our held-out wrists and/or fists. If it jumped off, it fell straight down, flapping and hanging by the jesses and was swooped back up onto the wrist by a special technique described in the training manual. Ilka quickly learned to stay on the wrist. The rest of the time she stayed in the hawk house, ate her hand-delivered meals, and watched everything going on around her. She was basically trouble-free and non-aggressive, and she seemed to enjoy the attention we gave her.

Ron "mans the hawk"

Ron "mans the hawk"

Because they are so common and easily trained as capable hunters, the majority of hawks captured by falconers in the US are red-tails. But by law they are permitted to be taken only in their first year, before they are locked into uncooperative adult behaviors. They are also protected by state and federal laws and the US Migratory Bird Act. A falconer has to get a permit to harbor a hawk. We learned that the hard way! (More about that later.)

A falconer releases his trained hawk to perch in a tree or other high vantage point and flushes out the prey (sometimes with a dog). Then when the hawk kills the prey, the falconer has to track it down and trade the bird a ready-to-eat piece of flesh (usually from a previous kill) in exchange for the new kill. The experts say that hawks develop no loving bond with their captors, but will work for food and quickly learn to associate the falconer with a guaranteed meal. In other words, a hawk never becomes a pet.

Ron sets Ilka free

Ron sets Ilka free

The red-tailed hawk is revered in some native American cultures, and its feathers are considered sacred and often used in religious ceremonies. Falconry has been around for 4,000 years and can be traced to its beginnings in the Middle East and Far East. It used to be a quick way to fetch fresh meat for the family but is now is more of an art than a necessity. In medieval England, falconry became the sport of kings, and having a beautiful, well-trained bird was an incredible status symbol. Falconers were well-paid and well-respected. Today in the US there are about 4,000 hobbyist falconers practicing the art.

photo by biologist Jason Brooks

photo by biologist Jason Brooks

photo by biologist Jason Brooks

photo by biologist Jason Brooks

Red-tailed hawks are one of the most widely distributed hawks in North America. They inhabit open fields, deserts, prairies, marshes, wooded areas, bluffs, mountain forests, small towns and big cities, and even tropical rain forests. The northernmost birds migrate south during the winter.

They are very well adapted and hang around their established territory as long as it has a good food supply. About 85 to 90% of a red-tail's diet consists of small to medium-sized mammals such as mice, moles, ground squirrels, and rabbits; birds; reptiles like snakes and lizards; and occasionally frogs and fish.

Their eyesight is 8 times as powerful as a human's. With binocular vision they can see spiders and beetles from afar and can spy a mouse from a mile away!

They hunt by swooping down from a high perch, seize their prey with their long, sharp talons, and either land to swallow it whole or tear it to bite-sized pieces on the spot. Sometimes they fly off to a safer place before devouring it.

When not courting and mating, they are hunting or digesting food. In flight, the red-tail prefers to soar, conserving energy by flapping as little as possible. In strong winds it occasionally hovers (kites) on beating wings to remain stationary above the ground but is particularly adept at catching updrafts and thermals to gain altitude, where it lazily circles and glides at 20 to 40 mph. When it spots a juicy rodent, it lets out a shrill cry like a steam whistle...which terrorizes and freezes the prey for a moment...then it dives down at speeds up to 120 mph, and seizes it with its talons.

A hawk's talons are dangerous weapons. Once they grasp their prey, they don't release the death grip unless they want to or have been trained to release it for an instant reward (tasty tidbit). There have been cases of a falconer having to have his hawk's talons surgically removed from his arm, or worse.

Red-tailed hawks are sexually mature at two years but usually begin breeding around three years old. They are monogamous (mate for life).

In early spring their courtship is a spectacular display of aerial acrobatics. They literally fall in love! The pair flies together in large circles to gain great height while uttering shrill cries. Then the male plunges into a deep dive and immediately shoots up again in an accelerated steep climb, and if that isn't awe-inspiring enough, he repeats it over and over again! Then the lovers interlock their talons and spiral toward the ground...not unlike a wild and crazy couple who get married while skydiving...but the hawks don't crash-land.

Six to eight weeks later the female lays one to three eggs in the large stick nest that the couple constructed following the consummation of their marriage. Incubation takes about a month and is maintained almost entirely by the female, but the male hunts for both of them and brings food to the nest for her. When hatched the young are covered with soft white down. The babies (called eyasses) will eat beetles and worms, and of course rodents that mom and dad rip into little pieces and poke down their throats.

They remain in the nest for up to 48 days, keeping both parents incredibly busy. During the last 10 days or so, the overgrown teenagers appear as large as the parents. They practice flapping their wings and balancing in the wind on the edge of the nest, preparing for the moment of truth when they will launch themselves into the air. They become completely independent of their parents at about 10 weeks old.

The next year the couple will stay in their territory and use the same nest or rotate usage with their other old nests. They repair the large, flat, shallow nests with sticks and twigs about 1/2 inch in diameter. Over the years a nest can grow to measure 3-feet wide and 3-feet deep if it is situated in the crotch of a large tree.

An average red-tail weighs from 2 to 4 pounds, is 17 to 22 inches tall, has a wingspan of about 4 1/2 feet, and...if all goes well...a lifespan of 20 years.

The female is nearly 1/4 to 1/3 larger than the male. Adults have dark brown and auburn plumage on their backs and wings, but their underside is light with a mottled and streaked chest and belly, and a sprinkle of cinnamon down the neck and upper chest. When soaring overhead you can see that familiar broad, rounded, russet-red tail, hence the name. Their strong legs and feet are yellow with three toes pointed forward and one aft. They have a hooked beak with holes (nares) in it like nostrils so they can breathe while eating. Their beautiful piercing eyes are yellow-gold in youth but turn amber with maturity.

Ron & Ilka

Ron & Ilka

Sometimes a hawk is chased and heckled by a mob of smaller birds that feel threatened by its mere presence in their territory. It works! A biologist friend recently informed me that not only can the little birds outmaneuver the hawk and peck at it mercilessly, but they try to poop on its feathers. Poop can be disastrous (deadly) for a hawk. It cannot afford for its feathers to get wet and dirty, so it escapes their attacks as fast as it can.

A red-tail at Eric's building site

A red-tail at Eric's building site

Because they are larger than most birds, you can easily spot red-tails perched along the highway on telephone poles and fence posts. They are opportunists and have adapted well to human habitats. When they seize their prey and stay on the ground to eat it, they puff out their feathers, flare their wings in an hovering arch, and fan out their tail, to guard their meal. That is when they are the most vulnerable, so they dine and dash as fast as they can...and they don't even bother to leave a tip!

When their crop is bulging, they may not hunt for a day or two. The crop is a pouch, halfway between the mouth and stomach, where the food is stored and gradually released to the stomach. When all the juices and nutrients are extracted, the hawk coughs up a light-weight casting which consists of hair, little bones, and anything else not digestible. The casting material also cleans the crop before it's expelled. To maintain its health, a hawk has to eat whole animals including their blood, guts, organs, and all the trimmings. It would die on steak alone.

We had to regularly hunt for our captive hawk. Ron was busy working the mine, so I had to do some of the hunting. I am not the Sarah Palin type. I hate killing animals, or anything for that matter. One extremely hot day, wearing only a bikini, I donned my holster, gun, and a little game bag, and set out to find a small bird to shoot for Ilka's dinner. The kids were napping in the trailer, and Ron was nearby in case of emergency, so I ventured about a half-mile away and reluctantly shot a robin. On the way back, seemingly out of nowhere, I saw what looked like a dust devil coming right at me. Squinting my eyes to see a little better in the glaring sunlight, I could tell that it was a truck barreling up the dusty dirt road. Surprise!

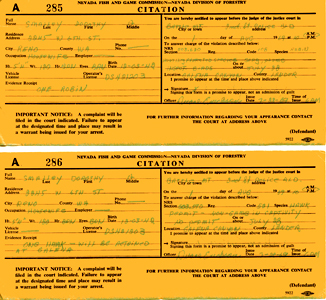

Dorothy's citations

Dorothy's citations

Pigmy cottontail

Pigmy cottontail

It turned out to be a desert ranger making the rounds in his designated god-forsaken territory. He screeched to a halt in a cloud of dust and asked, "What do have in the pouch?" I said, "A bird." He said, "Let me see it." Upon examination he determined it was a songbird and insectivore...both against the law to kill. He asked, "Why did you shoot it?" I foolishly said, "For our hawk." That did it!

He got out his ticket pad and wrote up two citations, then told me to get in and he would drive me back to the trailer so he could see the hawk with his own two beady eyes. We were busted! It was against the law to harbor a hawk and to kill a robin. While he was checking out Ilka, I excused myself and ran to the trailer to hide our little pigmy cottontail we had as a temporary pet in a cage. I was afraid having Bun-Bun would be off-limits too. (I found out later it was!)

The 4 baby robins

The 4 baby robins

Mr. Gruff Ranger turned out to be an OK guy after all. He gave me just warning tickets, and said to come into the sheriff's office before my court date, and he would prepare a permit for us. The very next day the kids and I went barreling down the dirt road in our old beat-up Ford Fairlane with the eight-track blaring Herman's Hermits...singing along with "Mrs. Brown You've Got A Lovely Daughter" all the way to Battle Mountain. (When you're young, everything is fun!) I paid the permit fee instead of a fine and became a law-abiding citizen instead of the lawless song-bird killer and hawk-harboring criminal I had been the day before. While I was at it I bought a fishing license but knew better than to ask if catching fish by hand was against the law.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, a friend had come to visit and thought he was doing us a favor by shooting a bird to feed our hawk. It would have been a favor, but he shot not only the wrong kind of bird (a robin again) but the wrong robin...the mother of a nest full of babies in a tree right outside our trailer. For a week I had heard them peeping nonstop and saw her flying back and forth all day with bugs and worms. Now she was dead, and I could hear the babies screaming for food. It was tragic! Oh what to do? There was only one thing I could do: become Mother Robin myself. And I did. The kids and I spent countless hours digging for worms, looking for bugs, and going back and forth to town to buy fresh beef to slice into worm-length strips to poke down their hatches. It was a full-time job feeding four babies every 30 minutes all day long! The only time they were quiet was at night when I would put the nest in a cupboard and shut the door. But in the early morning if I even jiggled the floor, they would feel the vibration and stick their open beaks straight up and peep peep peep for breakfast. It was much louder than an alarm clock, and there was no snooze button!

We managed to keep them fat and happy into featherhood, but then they wouldn't go away. I was their mother; they were mal-imprinted. I had no choice but to take them back to Reno.

It was a long, hot summer, but sadly it was coming to an end, and we were getting ready to pack up and move back home.

Ron had trained Ilka to hunt by using bird wings and other tempting lures on the end of a fishing pole, as he was instructed in the training manual. We figured she was finally ready to be set free. Click here to see hawk video.

The day we set Ilka free

The day we set Ilka free

She wouldn't go!

She wouldn't go!

We prepared to turn her loose in a carefully chosen spot with a shallow stream running through it, not far from the trailer. We said our goodbyes and good lucks with tears in our eyes, and then Ron un-strapped her jesses and boosted her aloft and heaved her into the air with all his might. But instead of taking off in a spectacular born-free flight as we had envisioned, she flew straight to me, landed on my shoulder, then fluttered up on top of my head. Intuitively we had never feared that Ilka would sink her talons in any of us (her adoptive family?), and indeed she did not. She simply skated around ever so gently, trying to balance on the ball (my cranium), which was the highest point in her immediate vicinity.

Ilka takes a bath in the stream

Ilka takes a bath in the stream

She flapped around for a while, then took off and flew over to the stream to check it out. Ron had read that hawks are very particular where they bathe. The water has to be the perfect depth, width, velocity, and temperature, or they won't dip into it. Evidently it met all the requirements, and she took her first bath. How lucky could we get! We were not only able to witness such a rare event in the wild but record it with our old silent-movie camera. Click here to see hawk video.

Going back to the trailer

Going back to the trailer

Ilka hangs out above the trailer

Ilka hangs out above the trailer

Cynthia & Ilka

Cynthia & Ilka

After her bath Ron attempted over and over again to launch her into the air for her maiden voyage, but she wouldn't take the hint. She finally hopped back onto his wrist and we all walked back to the trailer wondering what we were going to do with her.

Eric & Cynthia with tame robins

Eric & Cynthia with tame robins

Cynthia & Eric back to school in Reno

Cynthia & Eric back to school in Reno

We had valiantly tried to set her free...but she would not go. She'd hang out above our trailer on a dead branch and just sit there. Whenever we wanted her to come down from her perch, which was often, we'd put on the glove and hold it out with hamburger or some kind of dead meat hanging from it and she'd immediately swoop down with great accuracy and finesse, land on it, and eat. The kids loved this game even though she was so heavy they had to support her with both arms.

The day came to leave Galena for good. We packed up our menagerie and headed home. We decided we would keep Ilka in a backyard hawk house until she was ready to fly the coop on her own. And I had found a home for the robins. My mom said she'd be happy to provide a safe haven for them in her fenced and shady backyard.

All went well. Ilka seemed happy in suburbia and the totally tame robins followed mom around like the Pied Piper. They even went through her back door and into her kitchen where they'd jump up on the table for scraps. She'd had six kids herself and missed being mother bird, so she encouraged it! They eventually learned to fly and perch in her trees but never left her yard.

Ilka finally flew up, up, up and away one day after eating a fat gopher, and the last I saw of her she was a tiny dark speck in the bright blue sky over Reno, Nevada.

The summer of '69 was a memorable one indeed. Nobody got rich mining gold, but when the kids started school in September, they surely had plenty to talk about in "Show and Tell."